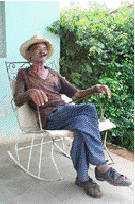

When doctors told retired civil engineer Clifford Dumont he had developed Arnfeldt tremor and ataxia syndrome (ATAS), a neurodegenerative disease first observed in 2005, he responded to the diagnosis the same way he had responded to the advent of cell phones, iPods, and the internet: “leave it to the kids,” he said.

“Some folks from my generation like to stay keen to the latest trends,” said Dumont, who is 86 years old. “Not me. If it wasn’t around before I reached middle age, I am not interested in it. That applies to movies, diseases, everything.”

Local physicians have tried to help Dumont accept his diagnosis by reminding him that ATAS is more treatable than many of the diseases he could have developed. But Dumont is skeptical of this claim. “These young docs act like ATAS is the best disease to come along since sliced bread disease,” he said. “I think they’re just happy they’ve got a snazzy new acronym to use.”

If Dumont had the power to choose, he would suffer from a more established ailment. “Give me Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, or plain old dementia,” Dumont said, “Those aren’t the diseases my grandson would get excited about, but they suit me just fine.”

According to Dumont, newer diseases such as ATAS introduce unnecessary complexities into the time-honored process of getting sick and dying. Multiple symptoms, paired with the cocktails of medications that are required to treat them, make for diseases that the elderly retiree could do without. “I don’t need some fancy-schmancy illness that ravages my body in fifteen different ways,” Dumont said.

“Sure, the geriatric diseases of my youth had their drawbacks,” continued Dumont. “For one thing, folks didn’t want much to do with you when you had them. But at least those diseases were simple. People would say, hey, stay away from that fellow; his brain’s gone to mush. And that was the end of it. Doctors these days won’t even allow you the solace of a mushy brain.”

Unfortunately for him, Dumont’s doctors say that his ATAS is here to stay. While Dumont learns to live with the disease, it’s his family that will bear the brunt of his frustration. “Since the diagnosis, he’s been calling me all the time, enraged,” said daughter Liza Dumont. “I remind him that taking five different pills instead of one is not that complicated. But then I remember that he’s from an age where there was only one pill: penicillin, I think. So it works best for me to try and convince him that he’s taking five of those.”